Prof Sunder Lal (b. 1934) obtained his MA (Mathematics) from Panjab University in 1958 and PhD from Tata Institute of Fundamental Research in 1965. He joined the Mathematics Department, Panjab University in 1966 and retired from here in 1994. He now divides time between Chandigarh and USA

–

I was born on 11 October 1934 in a small town called Tohana, then in Hisar district of undivided Punjab. It is now part of Fatehabad district of Haryana. I studied at District Board Middle School Tohana and passed my middle school eighth class examination conducted by School Education Board Lahore in 1947. I do not remember much about that time, but I remember very clearly that the school board did not issue any merit list for the examination, possibly because many answer sheets became untraceable due to disturbances and migration of population. For example, all of us in our school got zero in the paper in Sanskrit possibly because the examiner had migrated and therefore could not be contacted.

In order to continue our studies after eighth class, we had to move out to some other city as there was no provision for higher studies in our town. I joined Vaish High School in Rohtak, where I could not adjust to the hostel life, maybe because I had never lived alone away from the family; and the requirements in the hostel were harsh. I discontinued my studies and learnt bookkeeping in a script called Lande in Punjabi speaking areas and Mundi in Hindi speaking areas, which isactually a mutilation of Devanagari) used by businessmen all over Punjab and Haryana. Thus equipped, I started working as a munim in a timber shop in Kaithal then in Karnal District. I carried on this job for about four years thinking all the time about school and studies. I also hated the malpractices in business, for example when a beam of wood got damaged during transportation, the damaged portion was covered by bitumen and the beam was sold as blemishless. This incident shook me completely and I decided to give studies a try. Luckily my father agreed. I took private coaching for about six months for which I paid Rs.500.

I could not get admission anywhere, and appeared as a private candidate in the matriculation examination conducted by Panjab University. I appeared from Kaithal. Here are some interesting facts about that examination which I now recount:

- The University, for the first time, conducted the matriculation examination in 1952 in two shifts. We the private students appeared in the evening shift, of course with a new set of question papers.

- The University declared the result on May 3, 1952 without the merit list. The Tribune published the result without the photograph of the topper, a departure from the past.

- I think I remember correctly that the Tribune of May 3, 1952 carried an article by Sh. Bhupal Singh, Registrar Punjab University, arguing for the abolition of private candidacy of at least male students.

- The merit list was published on 21 May 1952 in The Tribune along with my photograph and the photograph of the girl who topped among the girl students only. The Tribune staff must have put in a lot of effort to get my photograph and some information about me as we had shifted away from Kaithal. The big error in the information published about me was that the name of my father was mentioned as Krishan Lal instead of Kishori Lal.

The merit list was delayed possibly because the fact that a private candidate was the topper was not acceptable to the powers that be in various controlling bodies of the University. At the behest of some influential people, our papers were being checked again and again possibly to bring my score down. Here is some proof of this. I got my matriculation certificate showing my marks at 729. After sometime this certificate was recalled and modified showing my score at 727 signed by Sh. Bhupal Singh in ink. Fortunately my merit position did not change.

- As a result of my performance, the lobby led by private coaching institutes supporting private candidacy won and status quo continued. This made the university administration think of ways to get rid of the heavy workload of conducting the matriculation examination.

- I recount an interesting incident, horrifying for me. That is the gazette of the matriculation examination on May 3, 1952 did not show the marks of those whose names were expected to appear on the merit list. The word S.C. (scholarship case) was written against their names. My father asked the school headmaster at Tohana as to what it meant. The headmaster was also not aware of the abbreviation. He told my father that possibly it was a suspect case – you can imagine the hell that broke loose after that. Luckily I was not thrashed.

- The candidate who topped the matriculation examination used to be awarded the University medal at the convocation. Those days the convocation was held invariably in the month of December at Ambala Cantt, from where The Tribune was also published. At that time I did not wear pants so when I went for the rehearsal wearing shirt, coat and pajamas, I was looked at curiously and somebody asked me if I would wear pants the next day for the convocation. The Matriculation topper used to be the only person who could not wear the ceremonial gown. Since I was to be the first person to receive the medal from the chief guest I was asked to be very careful and made to rehearse more than once.

- At Ambala Cantt. I stayed with some friends in the hostel of Sanatan Dharam College Ambala Cantt where I was told by many students that my initial score in the matriculation examination was 732.

After Matriculation examination I joined Vaish college Rohtak as a science student as insisted by my elders. They wanted me to become a civil engineer. Those were the days when Bhakra canals were being constructed in our area. Jobs were easily available and were popular as most of the engineers were seen to be making lots of money. However I had different ideas and therefore to kill the possibility once and for all I shifted to arts. After this my stay at that college was uneventful, I was no longer topper material, as arts students never topped. The college authorities were kind enough to continue to help me financially.

I joined Dayanand Anglo-Vedic College at Ambala City where my main subjects were Mathematics A-course and Mathematics B-course. Those days mathematics which is now one subject in B.A. was equal to two subjects. In the college I had a class fellow named Ved Prakash Dhamija. Both of us wanted to do honours in mathematics, for which the College did not have sufficient staff. Principal Bhagwan Dass was very kind and supported us all along financially and otherwise. He and Shri Vidya Sagar, possibly seeing the potential, offered to teach us before or after the regular college hours – I salute them. We came up to their expectations. Ved Prakash stood first in A-Course Honours and I stood first in B-Course Honours. Both of us got university medals. Unfortunately, after his BA Ved Prakash did not pursue his mathematics for family reasons and we lost a good would-be mathematician. He however obviously influenced his daughter Seema Dhamija who studied physics at Panjab University Department of Physics and got her PhD.

After B.A. Honours, Panjab University Department of Mathematics at Hoshiarpur was the obvious choice for doing M.A. in Mathematics. I could think of this because of a new scheme of a small number of merit scholarships of Rs. 100 per month announced by Dr. A C Joshi who was at that time Director of Public Instruction Punjab and later became Vice Chancellor of Panjab University. I should have been one of the first ones to get the scholarship but did not get it because my application was not forwarded in time from the Principal’s office possibly to favor a student next to me. Technically we were students of Panjab University College Hoshiarpur ; I wanted to complain and pursue the matter, but was advised otherwise. This forced me to work as a tutor for a few months so that I could afford to stay in the college hostel.

After some time I left the college hostel and started sharing private accommodation with PD Gupta, Raj Pal Gupta (both students of the Department of Physics) and Awtar Krishan (student of the Department of Zoology). The time spent with them was most fruitful and enjoyable. After completing their MSc Honours, both PD Gupta and Raj Pal migrated to USA. Awtar Krishan migrated to USA after completing his PhD at Panjab University. He visits Panjab University frequently and is well-known in the Departments of Zoology and Biotechnology. By the way, in Hoshiarpur at that time hundreds of students had to stay outside the hostels as sufficient accommodation was not available. Moreover staying outside was less expensive as compared to stay in the hostel.

At this time I came in close contact with SDM Ahuja who was a student of physics and whom I knew from Kaithal days. We were both research scholars in our respective departments at Chandigarh.

Till 1956, the examination in mathematics was conducted at the end of instruction of two years after BA/BSc and consisted of six papers of 100 marks each. Those who passed their BA or BSc examination in 1955 and took admission in MA Mathematics were required to appear in eight papers, four in MA Part- 1 at the end of one year and four at the end of second year, provided they had passed MA Part-1. The style of paper setting and marking was also changed. Earlier a student could attempt as many questions as they liked and if the total exceeded 100 marks they could be awarded 100 marks. In MA Part-1 and Part-2 the paper was divided into two parts. From Part-1 which was based on the prescribed syllabus, a candidate could get a maximum of 80 marks. The Part-II consisted of questions at the discretion of the examiner, the solution of which could be found sometimes only in research publications. The students of the first batch of the new system found the first paper of MA Part-1 on Real Analysis very tough. Almost all the students at various centres, except three at Hoshiarpur boycotted the examination. I remember that only three students out of few hundred completed the examination. In spite of their pleas no re-examination was conducted.

The above instance shows how tough the administration looking after mathematics in the University was. Professor H. Gupta and Dr. R. P. Bambah were trying their level best to build the department. This also shows that the whole situation appeared to be very scary to us. To start with, our class was quite large, but within a month more than half the students left the department. The scare described above and the speed at which our wonderful Real Analysis teacher (I liked him) taught contributed to this exodus. The times were tough for us, there is no doubt about it. Our classes were held from 9 a.m. to 1 p.m. without any break. Our request for a short break after two hours’ study was rejected outright, the argument being that studying mathematics required toughness. We had really no seniors with whom we could talk and get some help. Books were not easily available, especially in subjects like modern algebra. Luckily the teachers were helpful, if you were bold enough to talk to them. I took advantage of this facility very well.

To me it appears, the changeover from the old system to the new system was not very well planned. Our examinations were held in the month of September and the results came out sometime in October or November. This caused great hardship to the students. I shall give two instances. The Department of Mathematics shifted to Chandigarh in the summer of 1958. As a consequence, we had really nobody at Hoshiarpur to whom we could go to remove our difficulties/ problems that arose while preparing for the examination. After passing our MA examination, some of us wanted jobs as quickly as possible. Usually the main opportunity was to get lecturership in one of the colleges, but no such opportunity was available in October or November as the new session had already started in July and the colleges had filled up their vacancies, I was lucky to join as a research scholar even before my result came out.

At Hoshiarpur technically we were students of the college, which enabled us to use its facilities, but otherwise each department worked in its domain and there was no contact as such between various departments.

Before I conclude my recollections about our stay in Hoshiarpur, I would like to relate an interesting incident in our department. Strictly speaking, this is hearsay, backed by no evidence. There was one Dr. Gulati (sorry I forgot his initials) in our department, who had joined the Department on his return from abroad after obtaining his PhD. It seems the University had funded his trip abroad and he was required to serve the university for a specific period. After some time he got an offer from Delhi University, which he wanted to accept. His family circumstances were such that he had to go. Realizing his predicament the Vice-Chancellor Dewan Anand Kumar waived all conditions of the bond and let him go, notwithstanding the contrary view of the department. It was said that the Vice-Chancellor’s noting on the file went something like this – Allowed. He is not opening a grocery shop – going to teach, does not matter here or in Delhi. I wish I could see the file!

I joined as a research scholar in the department at Chandigarh. This was the time when lot of construction activity was going on in the campus in Sector 14. A few departments like Physics, Economics, and Mathematics were housed in a single building, that is the Department of Chemical Engineering. The offices of the Vice-Chancellor Dr AC Joshi were also in the same building. He took keen interest in everything that was going around. Usually he would say a few words whenever we crossed him. He was kind enough to offer a lift to the hostel, if it was raining and he saw one of us waiting.

In the beginning some of the research scholars were housed in a house number F-10 situated at the end of the residential quarters. This was a single house in the lane and beyond it on the western side was all jungle (now things are different). When I joined the Department another person with last name Shamihoke (I forgot the name) joined the department. In the house two research scholars were supposed to share a room. The authorities in the department wanted me to share a room with Shamihoke, whereas I wanted to live with a research scholar in physics with whom I had close contact in Hoshiarpur. This was resented very much, especially when I made it very clear that such type of interference was not on.

During my stay of about 10 months in the department I participated in a number of seminars and learned quite a few new topics. The seminars were regularly held in the afternoon after the regular classes were over. These seminars were attended by research scholars and faculty members, who were very enthusiastic and helpful. In spite of all this, I had an inner feeling to move on, possibly because I was convinced that the research scholars had no voice of their own.

Those days it was not difficult to get admission with financial support in American universities for higher studies, provided you could arrange the initial travel expenses. Knowing the financial position of my family, I did not think of this option at all, instead I applied to the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR) Bombay for a place as a research student in the school of mathematics in the year 1959. I could not do that in 1958, the year in which I got my MA degree, because by the time our result was declared, the selections at TIFR were over. I was called for an interview in the month of July 1959. I felt very much terrified when I saw the interview board consisting of Professors K Chandrasekharan, K G Ramanathan, Dr J R Choksi and two mathematicians from abroad, one a French mathematician (one of the early Bourbakis) and the other a British settled in Australia. We had heard stories of the toughness of Professors Chandrasekharan and Ramanathan earlier. The interview went on for three and a half hours or so in two shifts. Except for five minutes that were spent to know the reason for the break in my studies, it was mathematics all the time. Thank God I made it, but the letter of appointment made me jittery as it was stated that before joining, I would have to undergo a medical examination as required by the central government for senior jobs. My fear was based on the fact that I required very high-powered glasses for my eyes. In order to clear my doubts, I wrote to Professor K Chandrasekharan. The reply that I got was very pleasant and reassuring. I was told not to bother about the letter. I was also assured that once in Bombay, my eyes will be taken care of by the best possible eye specialist.

The first year at TIFR is a very tough one. A student is expected to attend two or three basic courses. A student is expected to answer questions even during the lecture sometime. Apart from the basic courses, a student is expected to be engaged in self study also. In my case, as I had studied some topics in Chandigarh, I was asked to give some lectures for which I had to prepare very hard so that I was ready to face the cross-examination. I was asked to write the notes of lectures of Professor F Bruhat from France, one of the Bourbakis. These lectures were published under the title “Some aspects of p-adic analysis”. To start with, we were three students in our batch. At the end of the first year only I was left in the Institute. Mr Ramesh Shukla, who was influenced by his brother Professor Umesh Shukla, who retired as professor of mathematics from Kurukshetra University, found a research career a tough one and left the institute on his own, joined the Indian Foreign Service and retired as the Indian Ambassador somewhere. The other student Miss Vasanti Bhat joined the University of Pune as a research student and completed her PhD there. When I met her last, she was a professor at the University of Bombay. The school of mathematics invited very distinguished mathematicians from all over the world to deliver lectures in their areas of research. I started taking interest in lecture courses related to the theory of numbers. Professor H Maass of University of Heidelberg, Germany delivered lectures on Modular Forms of One Variable. I wrote the lecture notes which were published later. I worked in this area under the guidance of Professor K G Ramanathan and got my PhD degree.

At the time of registration as a PhD student at Bombay University, I was told by the university office that MA of Punjab University was not recognized as equivalent to MA/MSc of Bombay University. This was the case in the year 1962/63, when the courses designed by Panjab University were in no way inferior to those of Bombay University. The authorities at the Mathematics Department of Panjab University were surprised, rather shocked, when this news was broken to them. Immediate steps were taken to rectify the situation. Luckily there was a provision that I could register as a PhD student on the basis of my BA degree, if obtained through an affiliated college of Panjab University. I wrote to the Principal of DAV College Ambala City requesting him to issue the required certificate, but got no response. This was really surprising in view of the fact that I had written that the Principal could ask any of the teachers in the Mathematics Department who would provide complete information about me. At this juncture, Sh Bhagwan Dass, who was my principal at the College came to my rescue. He was Principal, DAV College, Solapur (Maharashtra) and a member of the Senate of the University of Bombay. The University accepted his word about my graduation and registered me as a student of Ph.D.

The working conditions at TIFR are totally different from that of a department in any university. Every faculty member of the school of mathematics is engaged full-time in research and has no teaching responsibilities. Eminent mathematicians from all over the world visit the Institute regularly, deliver lectures and interact with mathematicians here. Members of the Institute also visit universities abroad to work with mathematicians interested in their field of research. While working at TIFR I always felt that along with research, it would be good if one had some teaching work apart from seminars etc. This view of mine got reinforced in discussions with Professor Maass who was a great supporter of the German system where every faculty member in a university, however senior he or she may be, would be engaged in teaching. Thus I decided to shift to Chandigarh to join the Department of Mathematics of Panjab University as soon as I got an offer in the summer of 1966. Of course the prospect of living in the newly planned City of Chandigarh was an added attraction.

Doing my stay of about 7 years at TIFR I noticed that once a person was found suitable for a particular position in the School of Mathematics, he or she would be asked to join immediately, the other formalities could be taken care of later on. For instance, Dr JC Parnami of the Department of Mathematics at Panjab University, soon after his MSc appeared before the interview board at TIFR to join as a research student. As soon as his interview was over, Professor M S Narasimhan came to my room and asked me to persuade Parnami to join right away. (His exact words were, ‘Don’t let that truck driver from your Chandigarh go away, ask him to join today itself’ – Parnami was well-built and had a moustache and hence the adjective truck driver.) He was a bit sad when we came to know that he had already left for Chandigarh without meeting me. I am almost certain that with the facilities available at TIFR and interactions that he could have had with more mathematicians from abroad, he would have achieved much more.

After joining the Institute I observed that TIFR did not have more or less any contact with mathematics departments of universities in India. This situation seemed to change after a while. To start with,the Institute started organizing Summer Schools every year for teachers and research students. The lecture notes of these summer schools were published. I also lectured in one summer school on algebraic number theory. Our colleagues in the department found these notes very useful while teaching a course on algebraic number theory. Later, the cooperation between the Institute and universities increased manifold.

My appointment letter as Reader in the Department of Mathematics Panjab University stated specifically that I should join on 13th July 1966, the first day of the new session, whereas the head of the department Professor H Gupta wanted me to join as early as possible so that I could familiarize myself with the new environment and also prepare my lectures etc. in advance. This new order asking people to join on a specific date might have been at the instance of the new Vice-Chancellor [Mr Suraj Bhan], who had come from a college and wanted to run the university like one. Earlier the situation was totally different. For example Dr VC Nanda from TIFR joined the Department just before summer vacation was about to start, an unthinkable thing in an affiliated college of the University.

To start with, the environment in the department was very healthy and left a deep and made a good impression on me. In the faculty meeting which was to decide the distribution of teaching work for the next session, the junior people and the new people irrespective of their position were asked to have their choice first, the seniors chose later (usually this is the other way around). The admission process to MA/MSc Part-I was very flexible. A student with low marks but having flair for mathematics could be admitted. The department also admitted school teachers teaching mathematics, who wanted to improve their prospects in the profession. These teachers usually spent three instead of two years in the department to complete their degree, but got high marks finally and prospered in the profession. Both these practices were given up after a few years. The first one because the department being Centre for Advanced Study in pure mathematics expanded rapidly and it was felt that distribution of teaching work would be better done by a small committee after seeking the choice of every faculty member. Usually the same topic was not allocated to the same person again and again. This healthy practice enabled us to learn many new topics. The second one had to be given up because of the public pressure on the University Administration. The admissions were now based strictly on merit list prepared by the office as per orders of higher authorities.

During my first year, I taught one full year course on number theory. Luckily for me, the class had quite a few very good students. This made me work hard and enjoy teaching. While one of the students joined TIFR and produced research work of high standard, the other got his PhD in the department itself. The teaching work load in the department was light for every faculty member, as a result of which each one of us had ample time to participate in seminars and pursue research activities. This yielded results as could be seen by looking at year wise list of research publications of the department.

As part of the activities of the Centre for Advanced Studies, it was felt that teaching of mathematics should be improved at the undergraduate level. For this the syllabus had to be revised, text books prepared and college teachers trained to teach new topics. All these tasks were undertaken in the seventies under the project COSIP (College Science Improvement Programme). After the revision of the syllabus, text books were written and published by the University Publication Bureau to keep the price low. Refresher courses were held to update the college teachers. This turned out to be a very popular program and enabled the department to update the syllabi at all levels without much opposition. At the later stages, the other universities of Punjab also participated. To start with, colleges of Haryana were also a part of the program, but around 1974 the Haryana government disaffiliated all the colleges situated in Haryana from Panjab University. This program was stopped in the mid-eighties and never revived, why, I don’t know.

During the seventies and eighties, the Centre implemented another program for college and university teachers, called The Faculty Improvement Program. Under this program, teachers of mathematics from different places of India came to the department and spent at least one year, learning new topics by attending regular classes with students and interacting with teachers. The UGC took the responsibility of paying their salaries plus some extra displacement allowance. This provision made it easy for teachers to get leave of absence from their respective workplaces. I can say without any doubt in my mind that this program proved very useful for everybody. Some of the teachers, who were earlier teaching in some remote areas, took up research work and headed University departments in some well-known universities. After some time, this program was replaced by another program, under which the lecturers, to get better scale or promotion, were supposed to attend a number of refresher courses (three or four, I don’t know exactly) organized by Academic Staff College in various universities. I do not know how useful this program was for the college teachers because they never agreed to any assessment criteria at the end of course. They listened to the lectures, got the certificate of successful completion and the matter ended there.

An important change that happened in the teaching departments of the University was the rotation of headship of a department. The person heading the department was designated as chairman of the department. The chairmanship was passed over to the next senior-most person after three years. This made the Vice-Chancellor very strong. Earlier many times some of the heads were of equal or even higher stature and could challenge the Vice-Chancellor easily. Many times the new people who took over did not have enough time at their disposal or enough contacts to get new projects or grants approved from various central agencies. It is true, a time had to come when working conditions in the department had to change, where everybody could play a role in the upliftment of the department and take care of interests of everybody in the department. The efficiency of the new system should have been evaluated say after 10 years or so, but it was never done.

I was in the department for more than 28 years. During all these years I found the working atmosphere to be very healthy. Everybody was willing to help everybody else to the maximum possible extent (a few exceptions maybe there, but they were negligible). I retired as professor in October 1994 at the age of 60. I wish the department goes from strength to strength and produces mathematicians of international repute.

…

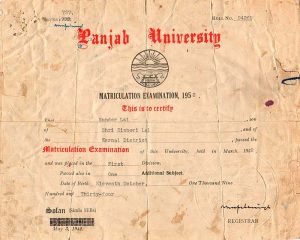

Matriculation Certificate of Sunder Lal issued in 1952 from Solan. Note at the top-left corner originally typed marks have been struck out and a new figure typed with the counter-signature of the Registrar.(see Text) |

News clip from The Tribune of 21st May 1952 announcing that Sunder Lal, a private candidate came first in the Panjab University Matriculation examination where more than 50000 students appear. |

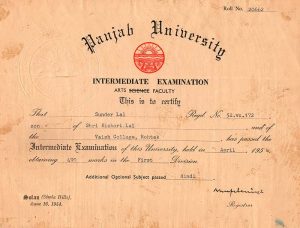

Sunder Lal’s certificate for Intermediate Examination which he passed from Vaish College, Rohtak in 1954 from Panjab University, Solan (Simla Hills). |

|

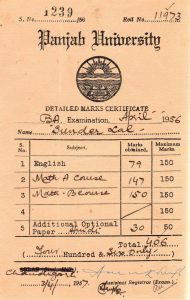

Detailed Marks Certificate from BA Examination issued in April 1957. Note that in the bottom left corner Solan (Simla Hills) have been struck out and Chandigarh written by hand. |

|

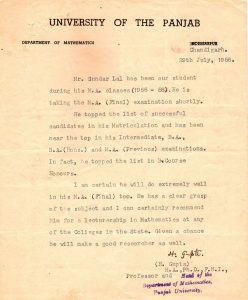

Testimonial issued to Sunder Lal in July 1958 by Professor H. Gupta, Head of Mathematics Department. In the letter head the name of the University is written as University of the Panjab, while the Department stamp mentions Punjab University with “u” in Punjab instead of “a”. Hoshiarpur has been deleted from top and Chandigarh is inserted. |